- Jul 27, 2015

- 5,458

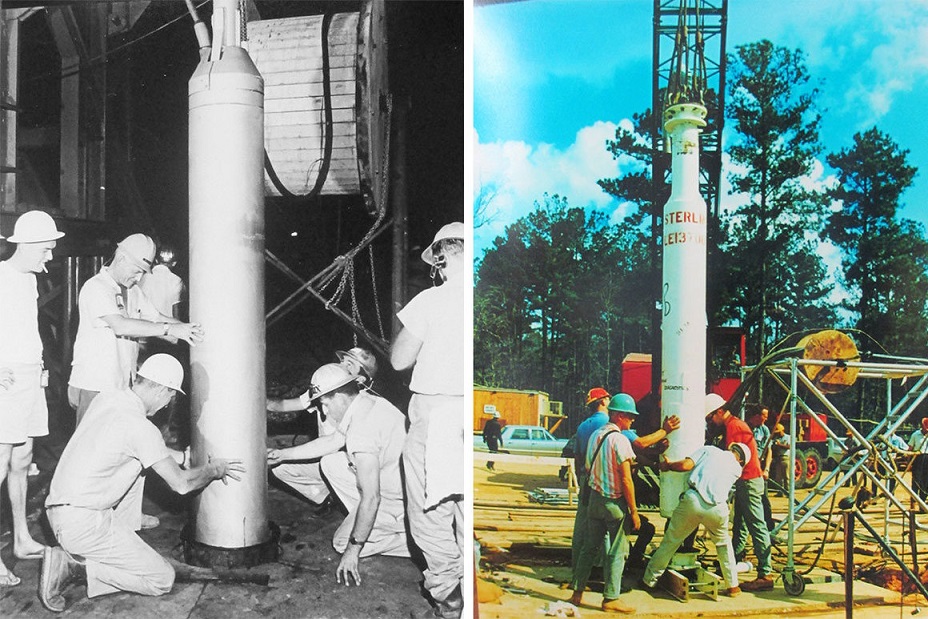

From left: Workers lower the 5.3-kiloton bomb used in the Salmon test into the ground; The second bomb was set off in the cavity gouged out by the first test two years earlier.

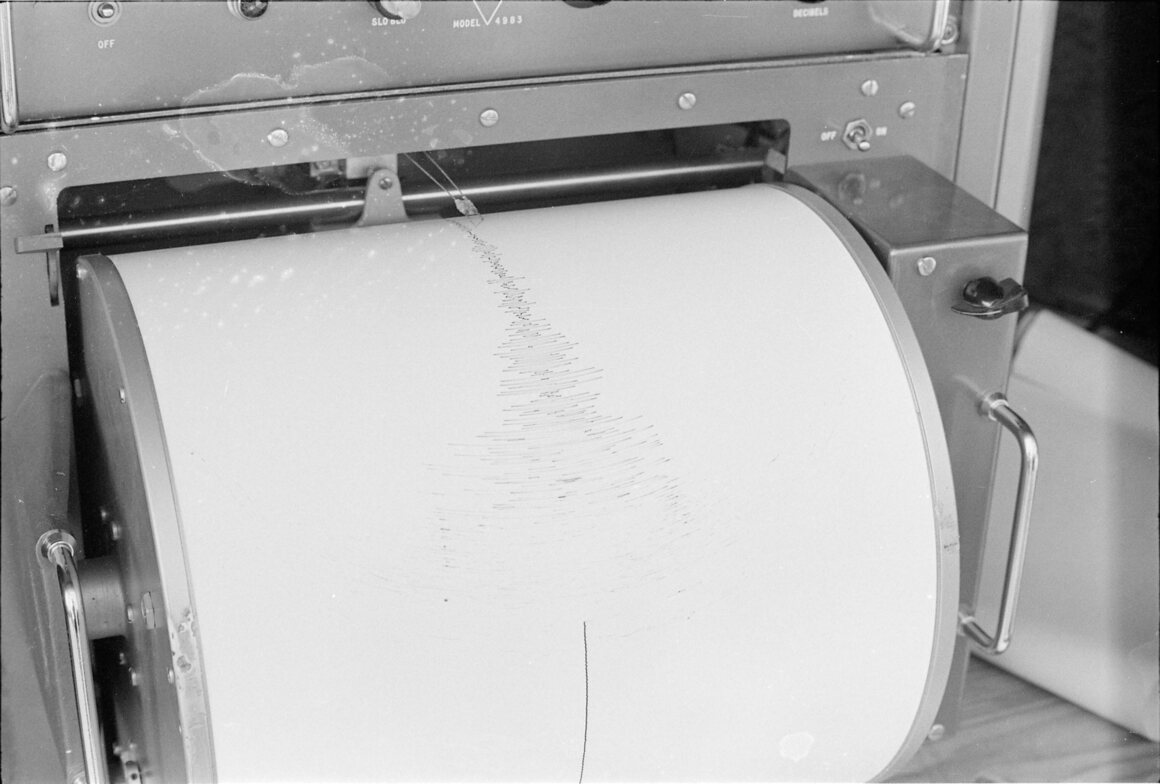

Quote : " By the late 1950s, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Britain were setting off atomic and hydrogen bombs on land, at sea, and in the air. The tests spewed radioactive fallout around the globe, fueling widespread public fears of cancer and birth defects. Pop culture was full of insects and reptiles turned monstrous by radiation. And the countries that did have nuclear weapons wanted to make it harder for others to join the club. So the nuclear powers started talking about banning bomb tests. And in 1958, experts meeting in Geneva proposed a worldwide network of sensors that would detect nuclear blasts, which appear on seismographs like earthquakes. But how could you tell if someone was cheating?

The idea of nuclear testing in an area with several medium to large cities nearby wasn’t universally popular. But Governor Ross Barnett was eager to host the AEC, even as he battled with the Kennedy administration over civil rights. “Barnett, even though he was a Dixiecrat and a segregationist, and one of the most vociferous, bombastic, and worst, was more than happy to welcome the image of Mississippi as helping to protect the United States from communism,” Burke says. And Breshears says, when she was growing up, Lamar County was “a small county, very patriotic.” “If the government told you the moon tomorrow night would be green, everybody would expect a green moon,” she says.

The first blast, code-named Salmon, was a 5.3-kiloton device that would blow a cavity into the salt dome half a mile underground. The second, Sterling, was only 380 tons, and would go off in the cavity left behind by Salmon. AEC crews drilled a 2,700-foot hole down into the salt dome, lowered the first bomb into it, plugged it with 600 feet of concrete… and waited. The Salmon test was put off nearly a month by a string of technical problems and bad weather, including Hurricane Hilda, which hit one state over in Louisiana. People living up to five miles from the test site were evacuated and recalled twice in preparation for blasts that never happened. They got paid $10 a head for adults and $5 for children for their trouble. Finally, at 10 a.m. on Oct. 22, came the boom. Steve Thompson and his family had cleared out of their house for a picnic at Lake Columbia, about 10 miles away. They watched a wave spread across the water—and then through the ground underneath them. “It was like being in a boat,” says Thompson, who was 15 at the time. “There was two big waves and a bunch of ripples.” To Brenda Foster, “It felt like the Earth just raised up and set back down.” “The windows on the house were shaking and rattling, and you could see the chimney on the house cracked all the way down,” says Foster, who was a few days shy of her 10th birthday. “That’s about all I remember of that, but I never will forget it.” In the aftermath, about 400 people filed claims for damages with the government, mostly for cracked plaster or masonry. On Nobles’s father’s farm, eight miles from the blast site, two wells quit working after the blasts. But one man, Horace Burge, found his house was “completely destroyed,” says Nobles, who was friends with Burge’s son. “It broke everything on the inside of his house, threw the stuff out of his cabinets, and messed his foundation up,” Nobles says. More than two years later, in December 1966, the AEC lowered the second bomb into the 110-foot hole gouged out by the first and set it off. The smaller device went almost unnoticed at the surface, and the scientific results weren’t spectacular, either. Far from Latter’s predictions that a blast as big as 100 kilotons could be kept off the scopes, Lewis says, it turned out that decoupling “is not a worry for anything but a very small explosion.” However, the data helped shape a later treaty which limited underground tests to 150 kilotons. And the fact that the tests were something of a wash is a good thing, Lewis says. A country that wanted to start building its own nuclear weapons isn’t likely to be able to conceal a test, even if it wanted to—and most aspiring nuclear powers, such as North Korea, are happy to let the world know they have the Bomb. “Iran has big salt domes,” Lewis says. “The last thing we would want Iran to do is have confidence in how big an explosion they could conduct without being detected. So there are some things we’d rather not know.”"