- Mar 29, 2018

- 7,883

Read the entire article here. It's long!It's that time again, when families and friends gather and implore the more technically inclined among them to troubleshoot problems they're having behind the device screens all around them. One of the most vexing and most common problems is logging into accounts in a way that's both secure and reliable.

Using the same password everywhere is easy, but in an age of mass data breaches and precision-orchestrated phishing attacks, it's also highly unadvisable. Then again, creating hundreds of unique passwords, storing them securely, and keeping them out of the hands of phishers and database hackers is hard enough for experts, let alone Uncle Charlie, who got his first smartphone only a few years ago. No wonder this problem never goes away.

Passkeys—the much-talked-about password alternative to passwords that have been widely available for almost two years—was supposed to fix all that. When I wrote about passkeys two years ago, I was a big believer. I remain convinced that passkeys mount the steepest hurdle yet for phishers, SIM swappers, database plunderers, and other adversaries trying to hijack accounts. How and why is that?

Elegant, yes, but usable?

The FIDO2 specification and the overlapping WebAuthn predecessor that underpin passkeys are nothing short of pure elegance. Unfortunately, as support has become ubiquitous in browsers, operating systems, password managers, and other third-party offerings, the ease and simplicity envisioned have been undone—so much so that they can't be considered usable security, a term I define as a security measure that's as easy, or only incrementally harder, to use as less-secure alternatives. "There are barriers at each turn that guide you through a developer's idea of how you should use them," William Brown, a software engineer specializing in authentication, wrote in an online interview. "None of them are deal-breaking, but they add up."

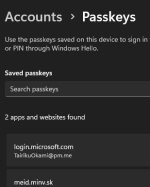

Passkeys are now supported on hundreds of sites and roughly a dozen operating systems and browsers. The diverse ecosystem demonstrates the industry-wide support for passkeys, but it has also fostered a jumble of competing workflows, appearances, and capabilities that can vary greatly depending on the particular site, OS, and browser (or browser agents such as native iOS or Android apps). Rather than help users understand the dizzying number of options and choose the right one, each implementation strong-arms the user into choosing the vendor's preferred choice.

The experience of logging into PayPal with a passkey on Windows will be different from logging into the same site on iOS or even logging into it with Edge on Android. And forget about trying to use a passkey to log into PayPal on Firefox. The payment site doesn't support that browser on any OS.

Another example is when I create a passkey for my LinkedIn account on Firefox. Because I use a wide assortment of browsers on platforms, I have chosen to sync the passkey using my 1Password password manager. In theory, that choice allows me to automatically use this passkey anywhere I have access to my 1Password account, something that isn't possible otherwise. But it's not as simple as all that ...

... What to tell Uncle Charlie?

In enterprise environments, passkeys can be a no-brainer alternative to passwords and authenticators. And even for Uncle Charlie—who has a single iPhone and Mac, and logs into only a handful of sites—passkeys may provide a simpler, less phishable path forward. Using a password manager to log into Gmail with a passkey ensures he's protected by MFA. Using the password alone does not. The takeaway from all of this—particularly for those recruited to provide technical support this week but also anyone trying to decide if it's time to up their own authentication game: If a password manager isn't already a part of the routine, see if it's viable to add one now. Password managers make it practical to use a virtually unlimited number of long, randomly generated passwords that are unique to each site.

For some, particularly people with diminished capacity or less comfort being online, this step alone will be enough. Everyone else should also, whenever possible, opt into MFA, ideally using security keys or, if that's not available, an authenticator app. I'm partial to 1Password as a password manager, Authy as an authenticator, and security keys from Yubico or Titan. There are plenty of other suitable alternatives.

Last edited by a moderator: