- Jul 27, 2015

- 5,458

The idea of analyzing faces with technology to confirm identities, make judgments, or predict behavior is nothing new. For centuries, facial recognition tech promised accuracy and objectivity. For centuries, it did something else.

Quote : " At Apple’s near-sacred product unveiling event last year, the iPhone X was undoubtedly the star of the show. Among its most boasted about features? The sleek device’s new security recognition system, Face ID. Rather than asking users to use their fingerprint on the now-nonexistent home button to unlock their phones, the iPhone X’s Face ID uses its cameras to make 3-D scans of their faces, which then enable them to unlock their phones by just holding the device up to their mugs.

At the event, an exec boasted that the facial recognition technology proved far safer than its previous fingerprint-based Touch ID, claiming that there’s only a 1 in a million chance of a random stranger’s face unlocking a user’s device. Enthusiastic users across the globe recorded themselves attempting to game the new feature. Nearly all failed: elaborate masks, lightning variations, makeup, costumes, and even twins tried to cheat Face ID, mostly without success.

The hype over Face ID’s futuristic promises of security with ease, however, may be undercut by more problematic recent applications of facial recognition technology. In September, for example, two Stanford researchers released a study that dubiously claimed that a machine-learning system predicted, with 74 to 81 percent accuracy, whether a woman or man was gay or straight based solely on photos of their faces. That same month, a team of researchers from Cambridge University, India’s National Institute of Technology Warangal, and the Indian Institute of Science presented a paper on a machine-learning system that they said could identify protesters hidden behind simple caps and scarves with success rates of about 69 percent. Both studies had their flaws but raised legitimate concerns about how advancing facial recognition technologies could be used to profile, intimidate, harass, or abuse vulnerable populations like minorities, political dissidents, and the poor.

We shouldn’t be surprised. As revolutionary as these capabilities may seem, the idea of analyzing faces with technology to confirm identities, make judgments, or predict behavior is nothing new. Instead, it seems faces are just back in vogue, and with a vengeance. Though they may have fallen out of favor in recent decades (dismissed as racist pseudoscience, as was the case with physiognomy, or edged out with other biometrics, such as fingerprints and DNA), over the past several centuries, humans have invested extraordinary amounts of resources trying to detect patterns in one another’s countenances that we think will reveal something about the people behind them. Faces have emerged in our imaginations as a sort of walking passcode of human nature, waiting to be deciphered and explained.

Creators of today’s facial recognition and analysis tools claim that their technologies are different. Powered by high-tech cameras and advanced algorithms, they hold out the promise of precision and scientific objectivity. But the past provides cautionary examples of the limits of such projections—showing how our conception of accuracy has changed, and how our use and misuse of these identification tools can come at great social costs.

For most of human history, people didn’t have sophisticated devices to recognize one another. Though that may seem obvious, in our digital age it’s important to remember just how much face-to-face interaction, and faces themselves, formed the backbone of modern society. The multiple components of the human face—the endless combination among muscles, nerves, and expressions, as well as the idea that it contained unique immutable identifiers (ones more reliable than names, signatures, clothing, or badges)—solidified our reliance on them as early standards of identification and trust.

The population growth and urbanization of the Industrial Revolution, however, rudely disrupted the reliability of knowing every face in a small community. Soon, finding alternative authenticators to recognize individuals became a matter of security for citizens and authorities alike. "

Quote : " The possibility of capturing something as complex as the human face on seemingly objective film (the camera doesn’t lie!) fed a sort of techno-utopian dream. Police officers saw mug shots as instruments that would revolutionize the way they could find and apprehend suspects. Criminologists leaped at the opportunity to use them to advance theories linking certain physical traits to deviant behavior. Governments embraced them as high-tech verification tools for passports, work permits, identification cards, and more.

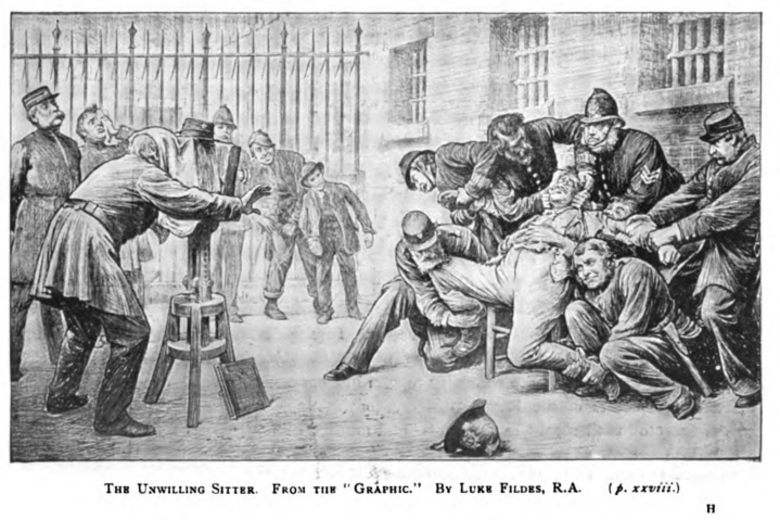

Soon, cameras moved from obscure photo studios into bureaucratic offices, police stations, and prisons so authorities could more easily capture portraits of citizens, suspects, and criminals for their respective files. But, at least at their start, photos weren’t as useful as authorities had hoped. Mug shots today involve highly standardized guidelines and front-view and side-view photos. Their Victorian counterparts, however, were more chaotic. Prisoners refused to cooperate. Heavy equipment had to be hauled around and repositioned. Portraiture and classification across institutions varied dramatically, making it difficult to share information between authorities. Plus, smart criminals could always alter their own physical appearance.

Around this time, a technique known as bertillonage emerged promising a standardized, foolproof biometric identification system. Designed by French police officer Alphonse Bertillon during the second half of the 19th century, his eponymous method consisted of the meticulous measurement of 11 parts of the body, including the length of the middle finger, the length of the right ear, and the length of the head. He suggested that these quantifiers, coupled with photography, could create a unique identifier for each suspect, criminal, or immigrant—one that could be easily stored, retrieved, and cross-referenced. Law officers soon took it on as a high-tech classification system.

In theory, bertillonage was an innovative breakthrough. In practice, it was a logistical nightmare.

After bertillonage flopped, facial recognition took a back seat to other more promising identification technologies. Fingerprinting soon took off as the biometric authentication du jour, first for criminal justice authorities, then commercial security systems, and later for personal digital devices (including Apple Face ID’s predecessor, Touch ID). Other biometrics, too, drew interest, including methods that authenticate identities through our voices, our irises, our genetic codes, and even by our walk.

In these intervening years, however, advances in facial recognition didn’t stop. Although it’s difficult to establish a proper birthdate for digital facial recognition, we can trace back some projects involving computers identifying specific markers on faces to the 1960s and 1970s. It took years for this research to become good enough to leave the lab. But by the 1990s, government agencies like state departments of motor vehicles began to incorporate facial recognition software to prevent identify theft and fraud in driver’s licenses.

Among the many ways the 9/11 attacks and subsequent “War on Terror” vastly expanded and changed mass surveillance tactics: It brought back facial identification as a preferred method of identification. Authorities expanded public video surveillance and analyzed massive troves of security camera and social media images. The federal government also invested heavily in developing new technologies. The FBI, for example, bet on its Next Generation Identification system, a database it describes as “the world’s largest and most efficient electronic repository of biometric and criminal history information.” It includes an automated facial recognition search and response system for law enforcement agencies.

The Department of Homeland Security, too, continues to turn to facial recognition as the next big thing in border enforcement. Last year, the agency took multiple steps to expand programs to collect facial and iris scans of international travelers at airports. It also issued a call for tech companies to submit proposals for a system that could passively scan the faces of foreign nationals entering and exiting the U.S. by car without needing to leave the vehicle, slow down, or take off hats or sunglasses.

Yet, as much as authorities tout these as neutral technologies meant to protect the nation, there’s an inherent tension that these systems work by literally attempting to sort out the faces of terror from those of ordinary citizens who, so the saying goes, have nothing to hide. "

Quote : " Yet beyond these rapid advances in accuracy, these latest technologies, too, come with potential for misinterpretation and abuse.

For one, these new systems are still far from foolproof. Each week, it seems, there’s a new report of a user beating Apple’s seemingly infallible Face ID: the masked researcher from a Vietnamese cybersecurity firm, the 10-year-old who inadvertently unlocked his mother’s phone, the woman in China who claimed to be able to unlock her colleague’s device (which some blame on a lack of diversity in tech). These examples remind us of the necessity of treating tech as an ongoing process that needs constant improvement. With hindsight, we can see how pre-digital predecessors to our modern facial recognition technologies failed as we recognized the biases of their creators (creating cameras and film optimized for only white skin) and their applications (like the “science” of physiognomy).

We can also see how they fell short as individuals inevitably found ways to hack the tools or to hack their own bodies to circumvent them.

For another, these technologies also come with great potential for injustice. With the ubiquity of technologies today and advances in computing power, this is perhaps more true now than it was historically.

Technologists developed the highly advanced systems of the digital age, for example, by exploiting expansive databases of personal information—information that wasn’t always obtained with the consent of the faces behind them. "

In the present, too, it’s easier to classify, search, and transfer enormous troves of biometric data—and it’s not always clear what gets shared between personal devices, corporations, and local, state, and federal government agencies. without reasonable limits, these systems that attempt to capture and authenticate a version of our bodies may belie our belief that we own them.

Full source : How Will Facial Recognition Tech Change the Future? Look at Its Problematic Past.