Does this new feature protects against DNS rebinding attacks?

It's not a new feature... it's the one I brought to your attention several posts ago.

Does this new feature protects against DNS rebinding attacks?

May I ask why not use NextDNS?@Parkinsond Thanks for one more thing, I had ControlD as a backup, but it seems that is sucked in the beginning and it still sucks now. I switched backup to AdguardDNS.

Neowin must be wrong then.It's not a new feature... it's the one I brought to your attention several posts ago.

You are always welcome@Parkinsond Thanks for one more thing, I had ControlD as a backup, but it seems that is sucked in the beginning and it still sucks now. I switched backup to AdguardDNS.

NextDNS is great; have been using for a while.May I ask why not use NextDNS?

I meant as a backup, sometimes NextDNS fails for hours, but I always had a trouble with ControlD, I blamed my tweaks, but clearly ControlD was to blame, it fails basics.May I ask why not use NextDNS?

That's weird. I've been using ND for years and I don't remember it failed before.I meant as a backup, sometimes NextDNS fails for hours, but I always had a trouble with ControlD, I blamed by tweaks, but clearly ControlD was to blame, it fails basics.

It happens once or twice a year, maybe during a maintenance, but still I would expect it to switch to another server. Once it lasted the whole day (PC+phone), unbearable.That's weird. I've been using ND for years and I don't remember it failed before.

Yes it is unacceptable.It happens once or twice a year, maybe during a maintenance, but still I would expect it to switch to another server. Once it lasted the whole day (PC+phone), unbearable.

B never fails to amaze me.Now BD has added a signature for the fake Chrome Updater

Trojan.genericS.11373

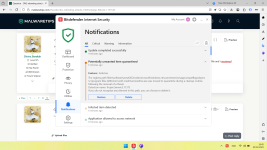

God BD is so stupid. To test that BD has added a signature for the fake Chrome Updater, I unzipped the file and BD instantly detected the infected file and i receieved "disinfection in progress", but when I checked BD notifications it seems that it deleted a OneDrive registry key as a potentially unwanted lol

View attachment 293500

It teaches you patience lol.B never fails to amaze me.

The Network Access Protection flag has actually been enabled by default in Brave since v1.54, released July 25, 2023. They pushed forward with it well before other major Chromium browsers.Does this new feature protects against DNS rebinding attacks?

Seems the new is moving from being optionally enabled by flag to be enabled by default for Edge, as described on Neowin.The Network Access Protection flag has actually been enabled by default in Brave since v1.54, released July 25, 2023. They pushed forward with it well before other major Chromium browsers.

The Network Access Protection flag has actually been enabled by default in Brave since v1.54, released July 25, 2023. They pushed forward with it well before other major Chromium browsers.

action:

type: block

condition:

resourceTypes:

- websocket

---Paranoid patients do not use MDIf, of course, you have a certain predisposition to paranoia...

Here are the main realistic ways DNS rebinding and WebSockets can interact, under the quite strict conditions where it’s actually exploitable.@Bot

Can you make me a table listing the specific ways in which a DNS rebinding attack could occur via websocket?

| Scenario | What has to be true | How WebSocket + DNS rebinding helps the attacker | Practical notes / mitigations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Internal web app exposes a WebSocket control API |

|

|

|

| 2. Router / NAS / IoT admin panel uses WebSockets |

|

|

|

| 3. Local development / debugging servers with WS (devtools, frameworks, DB dashboards, etc.) |

|

|

|

| 4. Internal apps using WS as a “thin RPC layer” over HTTP |

|

|

|

| 5. Legacy / misconfigured services that interpret WS handshake as HTTP |

|

|

|